“…The young Italian mezzo Veronica Simeoni sings Dido in lovely, well formed tones and is moving in the Carthaginian queen’s protracted death scene…”

by GEORGE LOOMIS

VALENCIA — More than half a century ago, Covent Garden’s landmark 1957 staging removed any doubt that Berlioz’s “Les Troyens” deserved a place on the opera stage. During the preceding hundred years, the opera toiled with intermittent success for recognition, eventually coming to exemplify the Romantic archetype of a masterpiece spurned in its day but exalted by future generations.

The five-act epic, grandly conceived with the Paris Opéra in mind, was never performed in complete form in Berlioz’s lifetime. Another Parisian theater staged Acts 3, 4 and 5, which deal with the Trojans’ sojourn in Carthage, under the title “Les Troyens à Carthage.” Sometimes, especially for concert performances, “Les Troyens” is performed over two evenings, with the first two acts labeled “La Prise de Troie” (The Taking of Troy). But for opera houses, a single evening is standard — more than five hours, including intermissions — as Berlioz intended.

That is how Valencia sees it in a glittering new staging with a production team drawn from the audacious Catalan theater company La Fura dels Baus. A co-production with St. Petersburg’s Mariinsky Theater and Warsaw’s Wielki Theater, it is currently winding up a five-performance run at the Palau de les Arts Reina Sofia, Valencia’s stunning, three-year-old opera house designed by Santiago Calatrava.

“Les Troyens” is a sublime work, with music that accords fully with Berlioz’s nobility of purpose. But it does go on. Part of the problem is structural. The ill-fated love affair between Dido and Aeneas in the latter part of the opera lacks the theatrical impact of the fall of Troy and the self-sacrifice of the Trojan women that come earlier, as well as the suspense leading up to these events.

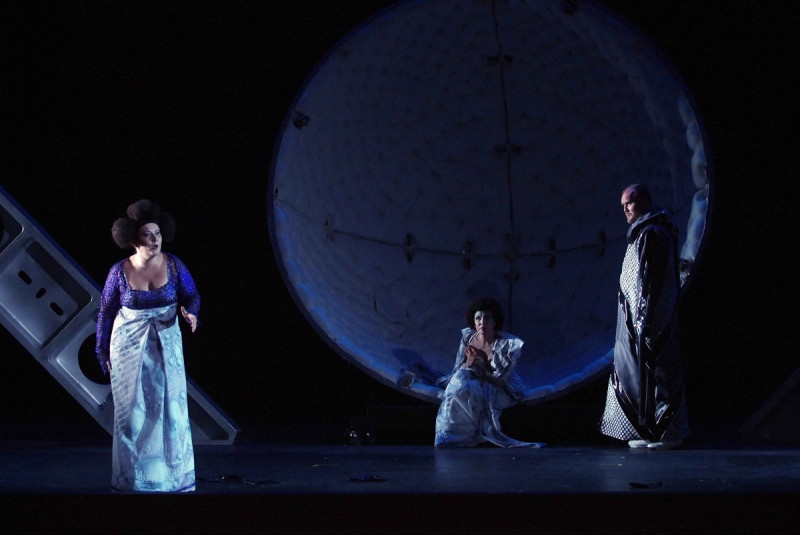

In the dazzling show by La Fura dels Baus, ancient myth meets Star Wars, and the eye is constantly engaged with images ranging from space-age technology to details of soccer uniforms. At the start of the Carthage scenes, Franc Aleu’s projections start with a simple kaleidoscope image, which gradually grows into what looks like a cathedral dome, as viewed from the ground, and eventually resembles a giant space capsule made in part of tubular balloons and metal ring-like octagons. Sets are by Roland Olbeter.

The Trojan horse, which Berlioz perhaps never intended to be seen, is a shining but frightening war machine, with an abstract head and wheels that allow it to move about for a chilling confrontation with the horrified Cassandra, alone with it on stage. Just before the mass suicide of the Trojan women, a hazy partition appears to separate them from their Greek would-be ravagers and blotches of blood soon appear on it.

Carlos Padrissa’s staging is not one to plumb the psychological depths of the characters yet the action is imaginatively thought out. In one vivid early scene Padrissa actually depicts the grisly death of the priest Laocoön, which Aeneas describes so graphically in his frenzied initial appearance. As the soloists and chorus react in horror to what Aeneas has said, two sea serpents descend from above to torment and eventually kill the helpless priest.

After witnessing this scene, one wondered whether Mr. Padrissa’s staging would go on to include similar episodes, especially during the slow-moving stretches of the Carthage scenes. In fact, it did not, but one can at least give him credit for not supplying action that contradicts the music. In their great love duet “Nuit d’ivresse,” Aeneas and Dido are stationary, standing next to each other, and are slowly lifted up to into an open sphere.

The young Italian mezzo Veronica Simeoni sings Dido in lovely, well formed tones and is moving in the Carthaginian queen’s protracted death scene. Stephen Gould sings Aeneas strongly but rather stolidly. His description of Laocoön’s death needed more excitement, and he left out the climactic high C in his aira “Inutiles regrets.”

The most compelling of the three leading principals is Elisabete Matos, whose delivery of the prophetess Cassandra’s vain pronouncements had real urgency and was supported by radiant tone. I wish, however, that she had remained in the dignified flowing black dress she wore during Act 1 (costumes by Chu Uroz) instead of changing into pants with soccer-style kneepads for her scene with the Trojan women.

Others in the cast include Stephen Milling, in deep voice as Dido’s minister Narbal; Eric Cutler, touching in the poet Iopas’s song of the field; Zlata Bulicheva, appealing as Dido’s sister Anna; Oksana Shilova, who made an impression as Aeneas’s son Ascanius; Dmitri Voropaev, in sweet voice as the homesick sailor Hylas; and Gabriele Viviani, as Cassandra’s disbelieving fiancé Coroebus.

Much of the pleasure comes from the pit, where Valery Gergiev leads a thoughtfully paced performance rich in detail and draws fine playing from the orchestra, hand-picked by Lorin Maazel, the Palau’s music director, just four years ago.

This is a worthy and often compelling “Troyens” even if it doesn’t shed new light on its stagecraft.

LINKLes Troyens. Palau de les Arts Reina Sofia.Valencia, Spain.